A survivor of the September 11 World Trade Center attacks still carries around a piece of steel from the catastrophe site. “I feel a part of me is missing when I don’t have it,” he explains. After experiencing a loss, a grieving teenager assembles leaves, twigs, and rocks to express thoughts and feelings she can’t quite put into words. Brenda Cowan, associate professor, Exhibition and Experience Design MA, has researched the mysterious ways we interact with objects, and developed a theory called Psychotherapeutic Object Dynamics. Her paper appeared in the spring 2017 issue of the peer-reviewed journal Exhibition, which is published by an affiliate of the American Alliance of Museums. Museum objects, she writes, long recognized as inspirations for reverie and epiphany, remain underappreciated as sources of healing.

Grounded in an extensive study of literature on the subject, Cowan began her fieldwork at Trails Carolina, a facility in North Carolina’s Blue Ridge Mountains that helps troubled teens. Away from the distractions of modern technology, young people at the center engage in “wilderness therapy”: The teens, Cowan writes, “assign a psychological burden to a rock, which they carry until they are ready to move into the next stages of healing. They will throw away, crush, or even burn the rock…. Using an object to eliminate life-restricting feelings of fear or hate thus becomes an action of deep change and growth, a reminder that the experience no longer holds power over them.” With assistance from the center’s clinical director of adolescent and family therapy and a professor of psychology who also works as a clinical therapist, Cowan tested whether such object dynamics existed outside the therapeutic context.

Partnering with the National September 11 Memorial Museum, Cowan’s team interviewed 11 people who donated objects related to the attacks. Donors tended to refer to these artifacts as “witnesses,” and to feel that the museum was an ally for stewarding them. The conversations, combined with observations at the North Carolina center, led Cowan to propose the five human-object dynamics, detailed below. She writes, “People examined the concepts of self and identity through associating memories and meanings with objects; experienced the concept of life continuum through giving, receiving, donating, and destroying objects; and communicated emotional states and thoughts through grouping, collecting, and making objects.”

Museums can encourage these healthful interactions, Cowan concludes in the article, which her teammates co-authored. Personal object donation initiatives, for example, can help build connections with communities and engender the “associating” dynamic. Shows in which visitors arrange objects within an exhibit allow them to benefit from “composing.” That’s just the beginning. “Museums,” she writes, “hold immense power to nurture and heal.”

The five object dynamics, revealed through 9/11 artifacts

Composing

It is critical to this survivor that the objects he donated (triage gown, stained shirt, ID badge, dirt from WTC site) stay together. Composing is the dynamic in which the physical interconnectivity of objects is essential to their meaning-making.

Associating

The dynamic of Associating is demonstrated by this First Responder’s need to carry a piece of steel from the North Tower in his pocket at all times. Without it, he feels lost.

Making

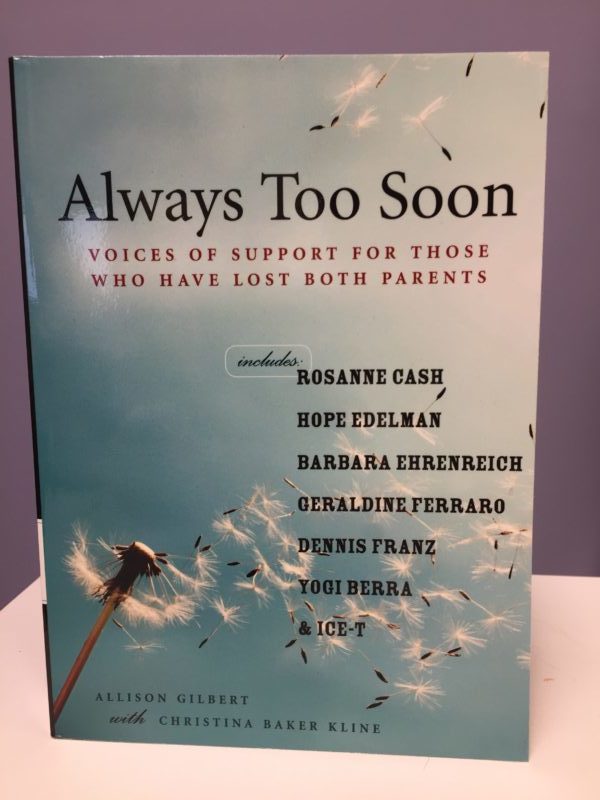

Journalist Allison Gilbert has written four books about loss and memory since being wounded on 9/11. For her, the object dynamic of Making is an ongoing part of healing.

Releasing and Unburdening

Removing from your life an object that has immense meaning is the dynamic of Releasing/Unburdening. The donation of these blood-stained shoes supported this survivor’s progression through the stages of trauma healing.

Giving and Receiving

The 9/11 museum received this crushed wristwatch from the wife of a victim, enabling her to experience the object dynamic of Giving/Receiving where an object’s meaning is held intact from the giver to the receiver. When an object is received with reverence, the giver is being affirmed within the life continuum and is being told “yes.”