From the late 1960s to the mid-’90s, horror novels ruled the publishing world. Stories about devil dolls, haunted villages, and giant insect attacks sported deliciously lurid covers, and sold millions of copies. A few years ago, author Grady Hendrix discovered The Little People, a long-forgotten paperback about Nazi leprechauns, and an obsession began.

He read 400 of these gore-soaked treasures, and wrote Paperbacks from Hell: The Twisted History of ’70s and ’80s Horror Fiction (Quirk Books). It includes art by Ed Soyka, chair of the Illustration Department; and Hendrix cites Vincent Di Fate, Illustration MFA faculty, as an important source for the book. On December 5, FIT hosted Hendrix and five book cover illustrators for an event celebrating the golden age of gruesomeness.

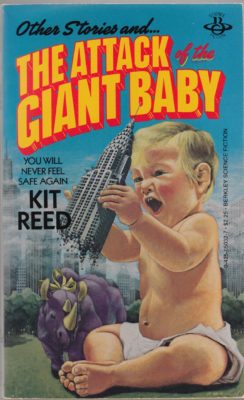

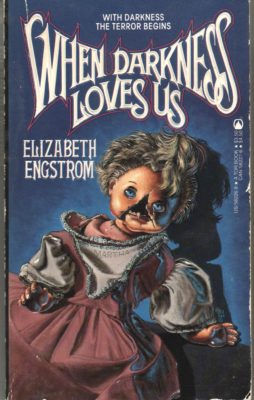

The political assassinations of the 1960s set the stage for the rise of horror fiction, Hendrix said, and the novels Rosemary’s Baby and The Exorcist (and their blockbuster film versions) officially kicked off the trend: “Satan had become publishing’s secret sauce.” Imitators soon arrived, including The Black Exorcist—“sort of like The Exorcist, only a lot cooler.” Tales of alien babies, murderous puppets, and blizzards of maggots found their way onto bookshelves. Where some see trash, Hendrix finds original ideas and, occasionally, true literary quality. “Michael McDowell’s Blackwater series is the One Hundred Years of Solitude of horror,” he said.

By 1996, digital media had transformed the aesthetic of horror book covers. The stories changed too, Hendrix said. Stephen King and V.C. Andrews dominated the market. After Silence of the Lambs, writers often portrayed serial killers as dandified intellectuals, à la Hannibal Lecter.

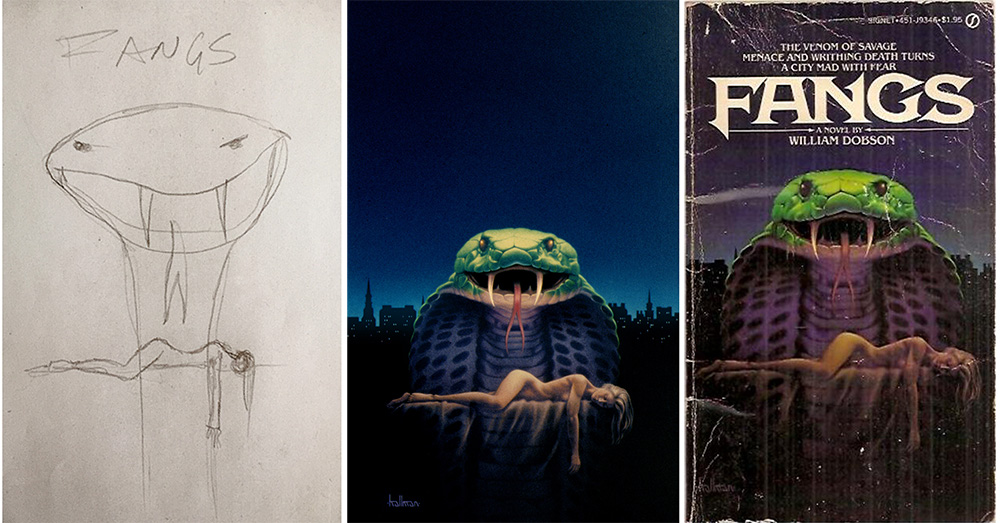

Hendrix asked the illustrators about their work from the ’80s and ’90s. Chad Laird, anadjunct associate professor who teaches a class about horror films in FIT’s History of Art Department, also shaped the conversation. The illustrators usually read the book, and had to create paintings several times larger than the jackets. Asked about sources of inspiration, artist Stephanie Gerber said, “I liked the emotions that artists like [graphic artist] H.R. Giger evoked—horrific, but attractive. I liked these two emotions mixed together.”

Library Associate Jane Mahoney organized this event as part of FIT’s Love Your Library program, a series of events intended to connect the Gladys Marcus library with students and faculty, and to raise its visibility in the public eye.