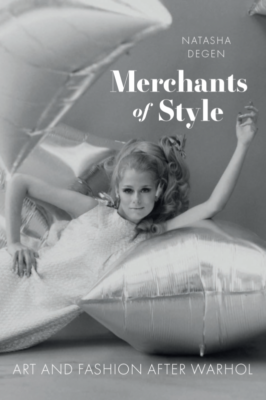

Fashion exhibitions have become an increasingly popular mainstay at museums—nearly 1.7 million people visited The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s 2018 show Heavenly Bodies, for example, making it the most-visited exhibition in the museum’s history. At the same time, major fashion brands such as Prada and LVMH have started foundations for displaying art. The work of Andy Warhol in particular prefigured many of these developments, says Natasha Degen, professor and chair of FIT’s Art Market Studies MA program. Her new book, Merchants of Style: Art and Fashion After Warhol, examines the convergence of art and fashion, and teases out some of its troubling implications. She answered a few questions on the subject for FIT Chief Storyteller Alex Joseph.

Alex Joseph: You make the case that fashion has a growing influence on fine art, but to quote Andy Warhol, “So, what?” What are you afraid of, exactly?

Natasha Degen: “Afraid” is a strong word, but I do think the art world has overlooked some of the risks inherent to opening itself up to fashion and embracing the blurring of boundaries between the two fields. On the one hand, art reaps many benefits from collaborating with fashion and luxury brands: financial rewards, visibility, mainstream relevance. These are huge. The art world is tiny relative to the fashion industry and has often been viewed, quite fairly, as exclusive and elite. On the other hand, there are downsides. The art that is used to advance commercial agendas often conforms to a specific kind of taste. It must be engaging and have strong visual impact, but it also must avoid alienating the public or challenging the political or economic order. And yet, art is uniquely positioned to challenge, subvert, critique … If there’s something to be afraid of, it’s that a more limited idea of art takes hold, that art begins to see itself differently.

Natasha Degen: “Afraid” is a strong word, but I do think the art world has overlooked some of the risks inherent to opening itself up to fashion and embracing the blurring of boundaries between the two fields. On the one hand, art reaps many benefits from collaborating with fashion and luxury brands: financial rewards, visibility, mainstream relevance. These are huge. The art world is tiny relative to the fashion industry and has often been viewed, quite fairly, as exclusive and elite. On the other hand, there are downsides. The art that is used to advance commercial agendas often conforms to a specific kind of taste. It must be engaging and have strong visual impact, but it also must avoid alienating the public or challenging the political or economic order. And yet, art is uniquely positioned to challenge, subvert, critique … If there’s something to be afraid of, it’s that a more limited idea of art takes hold, that art begins to see itself differently.

Several times you return to the idea that fine art should be “autonomous,” i.e., able to exist independent of the market. Yet isn’t this idea in some sense ahistorical? Artists have always had to please patrons, the court, and/or society, right? Why is our time different?

I chair the MA in Art Market Studies and my work largely centers around the history of the art market, so I’d be the first to admit that the idea of art’s autonomy—of art existing independently from, say, politics or the market—has always been vexed. Throughout history art has been shaped by the influence of its patrons, whether royal courts, the church, ultra-wealthy collectors, or corporations. Today is no different.

Nevertheless, art has long seen itself as performing a special role in culture. This self-understanding has allowed it to reject the normal rules and metrics of success, like popularity and price. It’s not always so cut and dry—the art we consider important is expensive, oftentimes—but there are other values that we take into consideration when determining art’s significance. Art need not serve a practical end—which gives it permission to be subversive and critical, and even suspicious of its own commodification. This is what’s at risk if art were to completely abandon the pretense to autonomy and transform into a cultural commodity indistinguishable from any other.

The art scene has notoriously excluded artists—I’m thinking of Alice Neel, whose figurative paintings were ignored in favor of abstract expressionists. Could the end of elitism be a good thing?

The end of elitism is a good thing if it allows artists like Alice Neel to succeed. In Neel’s day, abstraction dominated the art discourse—it was considered cerebral, profound, and, indeed, elite—whereas figurative painting was often overlooked or deemed peripheral. But even though figuration is more accessible (and thus may seem less elite), Neel’s painting is also challenging. She depicted difficult subjects—erotic scenes, psychiatric wards, pregnancy and childbirth—with startling candor.

The kind of populism I see taking hold today has elevated figures like KAWS, Daniel Arsham, Virgil Abloh—whose aesthetics not only harmonize with commercialism but often prove indistinguishable from it. They’re characteristic of a tendency I call “art pop,” which accepts commodification as a given. If Pop Art brought popular culture into the realm of high art, high art has now opened itself to popular culture.

I understand why people reject elitism as pretentious or, worse, exclusionary. But elite culture has its place. I’m reminded of Martin Scorsese’s comments about Marvel movies a few years back. The problem isn’t superhero franchises, it’s that the possibilities for art—for cinema as “an art form,” in Scorsese’s words—are narrowing.

You depict the funding dilemma for contemporary museums vividly. I will say I am one of the “omnivores” you describe: I ignore the splashier art shows in favor of smaller, more demanding ones—but I’m happy that museums can afford to offer both. How can museums better serve the public interest?

Public museums are in a tough spot. For many museums around the world, government funding is increasingly scarce. This means that they’re more reliant than ever on funding from private sources, whether individual donors or corporate sponsors, and on self-generated revenue from amenities and merchandise. And they face more and more competition—from immersive experiences devoted to beloved artists like Van Gogh and Klimt, to selfie fodder like the Museum of Ice Cream, to branded art foundations, like the ones I discuss in the book. These include the Fondation Louis Vuitton and the Fondazione Prada, which are extremely well-funded and, to their credit, very ambitious in their programming.

I see public museums as doing the best they can. They’re trying to strike a balance between exhibitions that win broad popular appeal (such as exhibitions of fashion) and those that speak primarily to a specialized audience. My concern is that the gap between public and private institutions is closing. The pressures on public museums to attract the donor class, find ways to self-fund, and attract large crowds has drawn the two ever closer. At the same time, public museums are rejecting the elitism they themselves have long embodied and questioning their own institutional authority. This makes them less didactic in the sense of patronizing their audience, but also less didactic in the sense of educating it. The story I tell in the book—that of the accelerating convergence of art and fashion—is ultimately part of a bigger story about the erosion of the public sphere. As it retreats, private enterprise steps into the void. With luxury brands positioning themselves as “cultural brands”—as cultural agents and impresarios—this trend looks set to continue unabated.