Most faux fur, made from synthetic compounds, is not biodegradable and can shed microplastics. A student research project holds promise for a better fur alternative.

Team Flora Fur—Isabella Bruski, Advertising and Marketing Communications, and Noah Silva, Fashion Business Management—are experimenting with using milkweed and flax to create a luxurious “fur” from 100 percent plant material. On June 21, Flora Fur won the Stella McCartney Prize for Sustainable Fashion at the Biodesign Challenge Summit, an international student competition focused on the future of biotechnology.

“The fact that it’s not biodegradable is the last argument used against faux fur by the fur industry,” Bruski says. “We wanted to create a faux fur that biodegrades.”

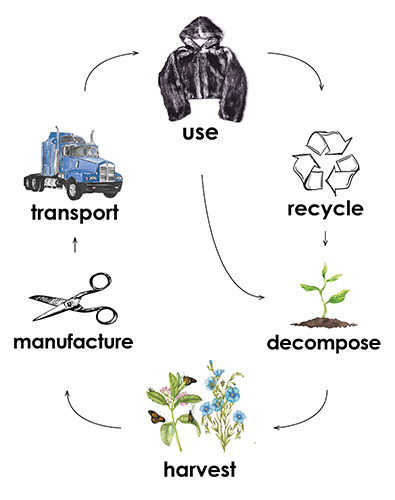

The students, both vegan, became friends during their first-year orientation in 2018. As soon as they learned about the Biodesign Challenge, they decided to create an animal-free product, and in doing preliminary research, Silva learned that the silken filaments crowning milkweed seeds were already being used as a replacement for goose down. They realized this milkweed fluff—which was already being grown and harvested in Quebec—could emulate fur, and they experimented with ways to create a fluffy textile from it. Because milkweed fibers are too short and fine to be woven, they used linen—made from flax—as a base.

Milkweed happens to be the only food source for monarch butterflies, a threatened species. Thus, the students reasoned, producing Flora Fur would help revive butterfly populations.

“What’s unique about Flora Fur is they’re using this common, weedy plant to make a luxury item,” says Assistant Professor Evelyn Rynkiewicz, an ecologist in the Science and Math Department, and advisor for the Biodesign Challenge. “They call it a weed because it can grow anywhere—which is a good thing in this case.”

Rynkiewicz connected them with additional FIT faculty who could help refine their idea. Jeffrey Silberman, chair of Textile Development and Marketing, supplied them with milkweed fiber and introduced them to local artisans to spin their yarn. Nomi Kleinman, chair of Textile/Surface Design, suggested incorporating linen and taught them weaving techniques to create their sample. And Associate Professor Deborah Berhanu, a materials scientist in the Science and Math Department, advised them on coating the fabric with nanoparticles of gold and other precious metals, which could dye it without chemicals and with less water, and could serve as a flame retardant.

Emboldened by the Stella McCartney honor, Bruski and Silva hope to refine their prototype, to develop a fabric that could eventually replace fur. From there, they may target other plastic-based materials.

“There are so many materials in plants that we haven’t considered before,” Bruski says. “Instead of trying to find new ways to fix plastic, we can be looking to all of these plants.”